And what is he making all night under the bulb?

His bench is stained.

His rags are soaking.

-William Stobb

from “The Owner’s Garage”

You drive by these buildings your entire life and you have no idea what’s going on inside of them. Concrete. Brick. No windows. No neon. Drab colors. If you drive by them at night, you shudder at the possibilities; you can think only of twisted behavior that needs to be kept from the community. Even the streetlights, with their sickly light, unnerve: what they illuminate and what they don’t. I met up with Justus Poehls at 400 S. Linwood at one in the morning last Friday. He told me to go around back and come in by the loading dock. I should acknowledge now, for transparency’s sake, that it has occurred to me before that he might have the urge to kill me every once in awhile.

Poehls shares tenancy with Labor Management Council of Northeast Wisconsin, Procon Data Systems, Verstegen Technical Sales and Ash Equipment, among others. The Labor Management Council may or may not oversee the Bedbug Registry, and I like to imagine that Ash Equipment works primarily with ashes somehow or other, but nobody stayed that late in the offices on that particular night for me to ask.

Poehls doesn’t keep odd hours; he keeps all hours. He teaches class at Fox Valley Technical College, had worked stacking lumber before I met up with him, parents four rambunctious children with his wife, Laura, and makes pictures every opportunity he gets—even if that opportunity comes when the rest of the city is in the tavern or in bed.

The first picture he showed me featured his wife. She doesn’t look right at you but looks like she could tear your heart out (or did to mine, at least). In real life, you might not suspect she would be capable of such a thing, or if you were to suspect such a thing, you would really only process it subconsciously. She bowls you over with her generosity, with how closely she listens to everything you say. But in the frozen image Poehls shot directly onto a tin plate, she eviscerates you.

After showing me that portrait, he offered me a High Life from the twelver of bottles he had sitting on the floor by the steps leading out into all the other office spaces, and—I would vitally learn—the pisser. The next shot he unveiled I’d already seen: the Wisconsinite gone Hawaiian then Wisconsinite again, known locally these days as the Honey Huntress, Laura Faith, looking like she’s just witnessed a sex act she’d never imagined. Or a stabbing maybe.

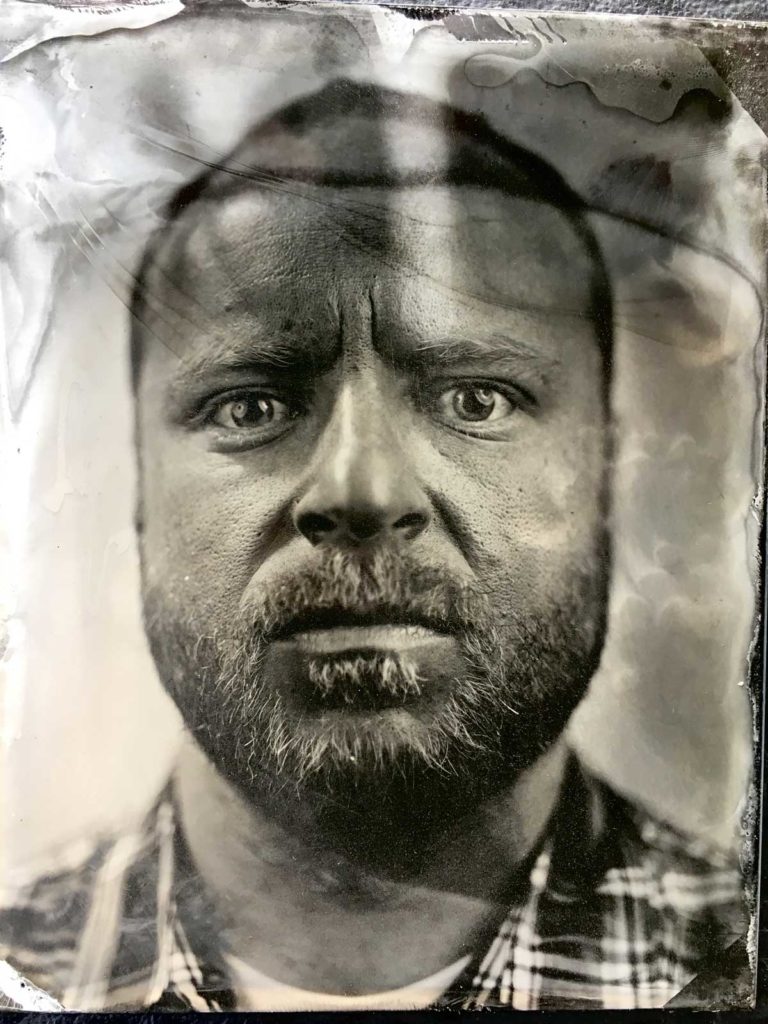

Did I mention that Poehls makes these pictures behind the actual loading dock door of this crummy building (all apologies to Ash Equipment)? That he shoots them directly onto tin, glass and old, obscure photo paper? Figuring the chemistry as he goes? That someone’s graffitied “DAN’S PLACE” on the rafters? That on the night I show up it’d rained so much that Poehls’ leased roof had leaked and he was now drying the giant Doc Brown or Tesla-invented battery he uses to power his incredible camera so that he could take my picture? Lastly, did I mention that this is mad science going on in your city?

With the casual flirtations behind us, Poehls gets down to business: he shuts out the lights. An anxiousness eats at me, but it doesn’t have anything to do with fear, just anticipation. How often do you get the sensation of standing in the middle of a pitch black room, nearly absolute quiet, unmoored, awaiting? Positively invigorating, I tell you. And out of that black—somehow not as rich as the black in Poehls’ photographs, more of an emptiness or absence, an honest absence of light and a moment or two of questioning your existence… maybe reality… maybe it’s just the beer.

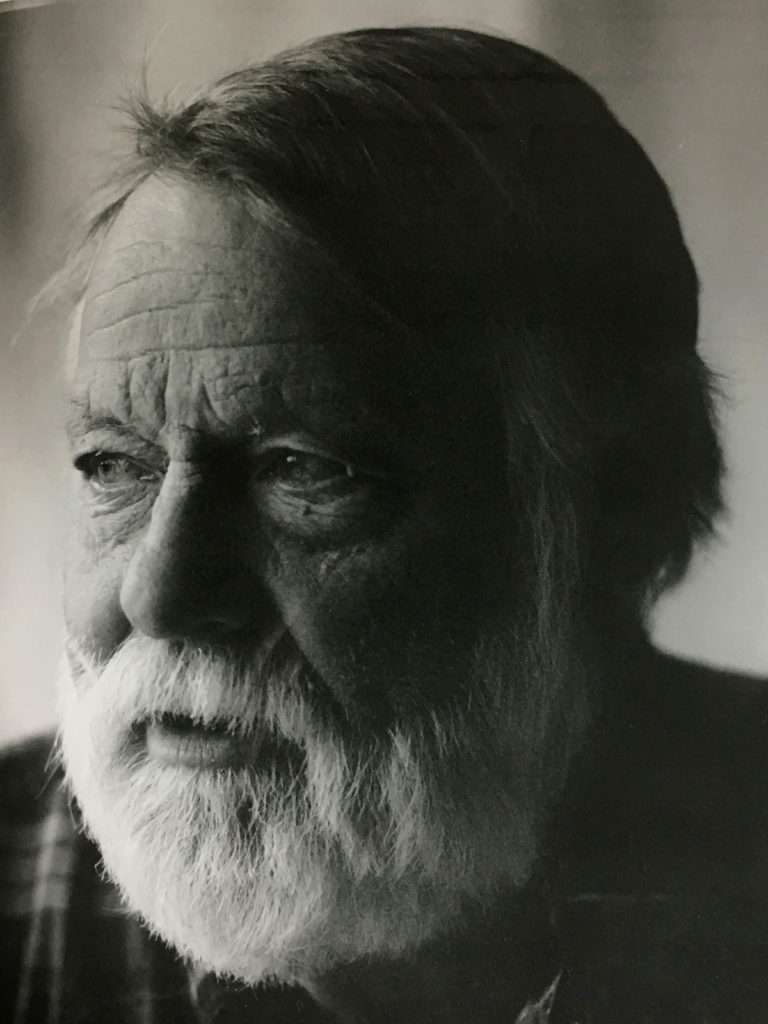

Poehls lifts up spirits like a goddamn charlatan. His work is not gothic, but otherworldly. You watch the canvas take a couple of baths and then there’s his mother’s whole soul, her furious eyes, her lived-in beauty (yes, his mother bewitches), and he’s got her holding a fucking branch in front of her face, partially obscuring it. She’s here and now Queen Jocasta. Holy Hell. Everybody’s mother deserves this kind of Poehls portraiture treatment. You see that soul materialize and you start to think that maybe, just maybe, Poehls isn’t stealing, but rather reappropriating. Purifying in a way. Making clear, making stark.

You don’t get the softened version of yourself if you get the privilege of having Poehls duck under his magician’s cloak to capture your image. You get your harshest self, the self you would wish for if you needed to keep your family alive in an apocalypse. You get perilous and beautiful. You get tragic and resilient. You get something akin to the way the world feels right now. In an age where everyone dabbles in picture-taking (have you seen the 4-H photo entrant exhibits at the Winnebago or Sheboygan county fairs), no one is precisely doing what Poehls is doing in that deserted space on Linwood: he’s letting you cold-cock the world with the image of you he concocts. And make no mistake, even though he gives himself only one chance with his Rube Goldberg-esque reinvention of the perfect camera, he knows just the right moment to hit the spot. That’s the thing about Poehls the photographer: he allows you the opportunity to confess something about yourself to the camera that you haven’t totally come clean about yet. He defies you to confess it. He quietly insists on it. The guy has strong feelings.

Then I see the picture of his daughter, Ramona (age three), cringing in the foreground while her five-year-old brother, Eli, threatens to clobber her from behind with something (the same branch Poehls’ mother tantalizingly half-hid behind?). It appears as though she’s being put upon and anguished by some deviltry (Eli, though possessed by some of the good ole piss and vinegar, contends for pie-sweetest, most hearteningly inquisitive kid in Appleton, if not on Earth, in my book). Biblical. That’s the power of Poehls’ really breath-choking photography when you see it: you get religion in it. No matter what, you would like to believe that an image of yourself found by your great-grandchildren decades from now would signify a complicatedness that might give them a feeling of pride.

The last exposure of the night that he teased out with the chemicals and water featured his only subject so far that I don’t know personally. He believed I would find her beautiful. The picture develops like a dream going from fuzzy and only vaguely familiar to feeling so real it shakes you up. You see a girl in a photograph created by a mad scientist in his laboratory, and she looks a whole hell of a lot like someone you knew, but you can’t put your finger on it. She wears a winter hat and grips her head: if that’s not Midwestern, I don’t know what is. She appears agitated, but not by the camera, by something that’s on her mind. My man, Poehls, somehow puts in the image “the something” that’s on your mind. How does he do that? It probably has something to do with the fact that he has something on his mind and usually he’s not willing to give it up.

I don’t know the girl’s name. I can’t remember if Poehls couldn’t remember or if he whispered it in the dark while I was transfixed and didn’t notice. We marvel at how he’s wound up with this small series of images of defiant women, fierce women, of women stewing, of women not just wanting to be seen (certainly not content as eye-candy). He tells me I should get home. Get home to my family? Get home to my trio of furious-minded girls? Or maybe he thinks I need some sleep because I’m getting slap-happy. Maybe he thinks I don’t need another High Life. Yeah, that’s it. He notes we’re out of beer.

In my car, before I key the ignition, with half of the dome on, I jot down: Vision is everything. From the outside the building looks abandoned. At his command, I fled, but the truth of the matter is that on the concrete just west and inside of the loading dock—in the dark—he killed me.

Learn more about Justus at his website: justuspoehls.com.

CREDITS

Text: Kory Kosmicki

Lead Photo: Ryan Eick